Muscle Hydration

Muscle Hydration

Couldn't load pickup availability

The Science of Hydration

Proper hydration starts with drinking water, but you don’t feel all the benefits until the water is available to the tissues that support performance. This is where electrolytes come in.

But before we get to that, let’s ground this in some basic physiology. Most of the water in your body lives inside your cells. The rest sits outside your cells in your blood and the spaces between tissues, which together make up extracellular fluid. Your body tightly controls how much water moves between these areas, since even small swings in cell volume can impair function.

Dehydration causes fluid loss from multiple areas. When you’re dehydrated, blood plasma volume drops, and your body moves water from your cells and between tissues into the blood. When you work out, minor fluid loss can cause cell shrinkage within 30–60 minutes — often before you even feel thirsty.

Shrunken cells have overly concentrated ions, enzymes, and other solutes, which slows muscle contraction, increases fatigue, and disrupts nerve signaling, making movements feel weaker and less coordinated.

Electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and magnesium make this fluid regulation possible:

- Sodium helps keep water in your bloodstream and sets the gradients that let water follow into cells

- Potassium helps keep water inside your cells

- Magnesium helps these two minerals work together efficiently

Here’s how each electrolyte optimizes hydration to keep you performing at your peak.

Sodium: The Signal Starter

Sodium is the main regulator of fluid balance outside cells — and the primary electrolyte lost through sweat. It helps you hold onto water in your bloodstream, which keeps plasma volume high enough to deliver oxygen and keep your body temperature and heart rate stable during training.

When sodium drops, plasma volume drops with it. Your heart has to beat faster to move the same amount of blood, your core temperature climbs, and your muscles fatigue sooner.

Sodium also plays a direct role in muscle activation. Each time your brain tells a muscle to move, sodium floods into nerve and muscle cells, sparking the electrical signal that makes the fiber contract. After that signal fires, your cells use a reset system called the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+) to push sodium back out of the cell and pull potassium in so the next contraction can happen.

When sodium runs low, this signaling becomes less efficient. You may struggle to concentrate, muscles will start to cramp, fatigue and weakness will creep in.

Potassium is the muscle conductor.

Potassium is the pull to sodium’s push. While sodium manages fluid outside your cells, potassium helps water stay inside them — keeping electrical signals sharp to facilitate muscle contractions.

Most of the potassium in your body lives inside your muscle and nerve cells. After a muscle fires, potassium is briefly pushed out of the cell so the muscle fiber can reset and fire again. This reset phase — called repolarization — is what allows muscles to contract rhythmically and with force.

Potassium also plays a role in fluid balance.When it drops to clinically low levels, your kidneys struggle to hold onto water. But exercise typically doesn't deplete potassium enough to cause that problem. If you're chronically low on potassium from diet or health issues, that's a different story. But for exercise hydration? Sodium does most of the heavy lifting.

Magnesium is your System’s ATP activator — your body’s main energy currency — to power the sodium-potassium pump. The pump only works when ATP is bound to magnesium, which means magnesium determines how efficiently your cells can generate and use energy during training.

Without enough magnesium, the sodium-potassium pump slows down and more sodium enters the cell. Electrical signals become less reliable, and muscles can’t contract or reset efficiently. You may feel your muscles spasm when you reach this state.

Pre Workout Hydration: Priming the System to maximize work outs!

Pre-hydration is one of the most overlooked performance tools. More than half of all athletes — from high school competitors to seasoned lifters — start training already under-hydrated.

Starting a workout dehydrated has three primary consequences:

1. Reduces performance capacity

Once you begin a hard workout dehydrated, it’s difficult to claw your way back. Your gut absorbs fluid within seconds but complete absorption into your bloodstream, muscles, and connective tissue takes minutes or even hours.

When you’re under-hydrated, blood plasma volume is already reduced. As exercise continues, fluid losses add up faster than your body can replace them. Strength, power, and endurance decline earlier in the session — often within 30–60 minutes — even if effort remains high.

“If you start hard training, and you continue training hard but your hydration wasn't in touch beforehand, you're gonna start to see decrements of performance hit somewhere between the 30-minute and hour mark,” Dr. Israetel explains.

2. Compromises thermoregulation

Starting a workout dehydrated also compromises thermoregulation. When you’re under-hydrated, you can’t move heat as effectively, so your core temperature rises faster. Your sweat rate drops — which makes cooling even harder. Fatigue hits faster, weakness creeps in, and you might start to feel dizzy or nauseated.

3. Increases risk of injury

Pre-hydrating also protects you against injuries. Proper hydration can affect the amount of fluid in your tendons and muscles, while dehydration can make tissues more susceptible to tears and strains.

The Formula: Drink water with electrolytes 2–4 hours before training.

The goal is to get water and electrolytes into your system early enough that it's distributed where you need it.

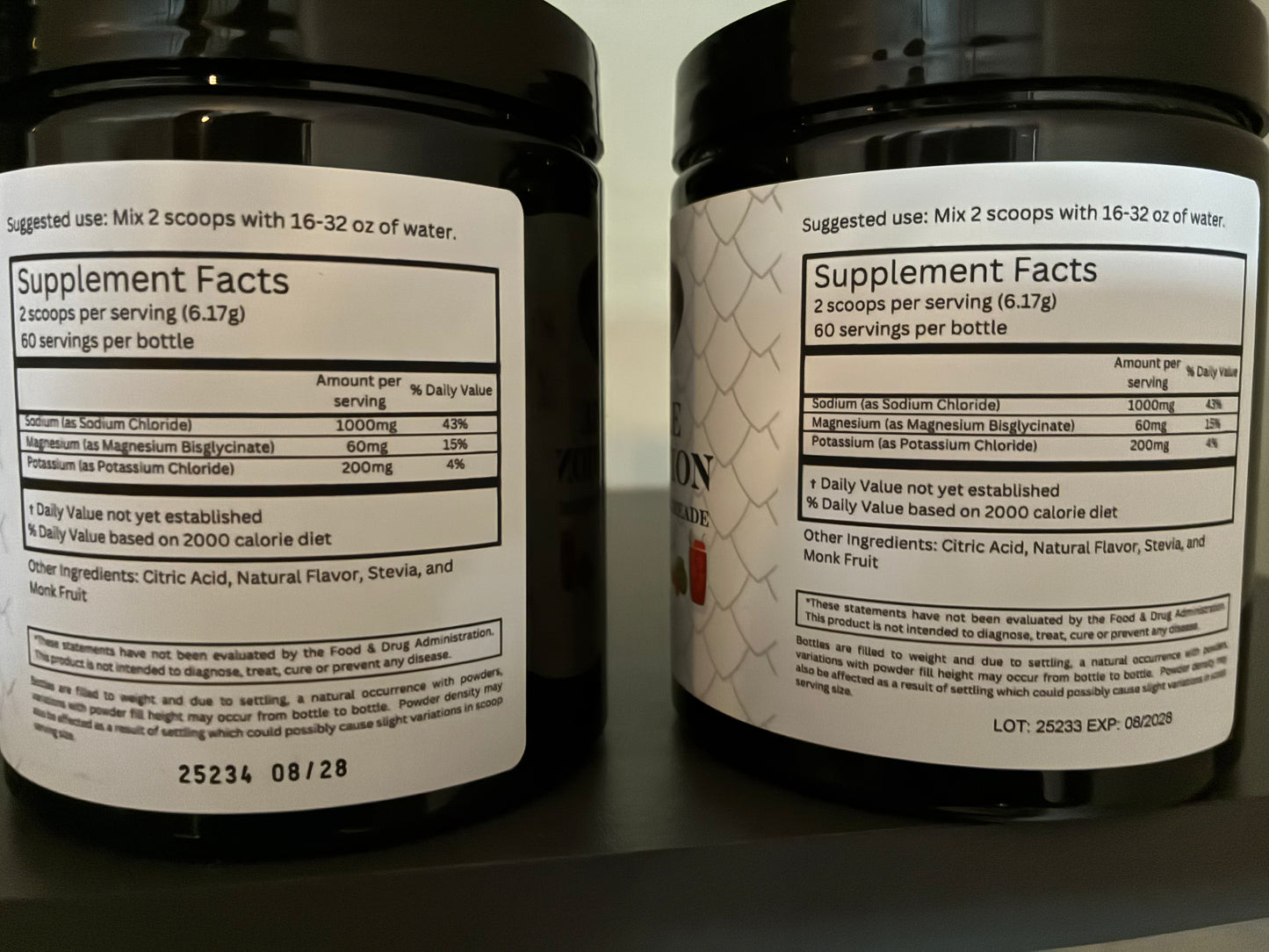

Standard approach: Drink .08–.15 oz of water per pound of body weight 2–4 hours before training. For a 150-lb person, that’s 1.5–2.5 cups of water (or 11.5–23 oz). Aim for ~500–1,000 mg sodium per hour during heavy sweating. This can come from commercial electrolyte mixes, salted fluids, or food sources, and will help water get absorbed and distributed. This gives your body time to raise plasma volume and hydrate tissues.

Early morning workouts: If you don’t have hours of lead time, research suggests drinking about 10 oz of electrolyte fluids 10-20 minutes before your work out, and then another 7–10 oz of electrolyte fluids occasionally throughout the day.

Heat or heavy sweating: Increase the quantities. I typically suggest adding 1 extra LMNT stick and between 20–40 oz of extra water. My average client uses 2 LMNTs daily and may add extra when competing in a competition or increasing activity levels.

These are all guidelines, not rules. Hydration needs vary based on sweat rate, environment, training intensity, and individual physiology. Adjust your intake over time based on how you feel and perform.

Keeping Hydrated during a work out: Keeping the Signal Strong

As soon as you start training, you lose both water and electrolytes through sweat. In an hour of exercise, a moderately heavy sweater loses about 1 to 2 liters of fluids and a few hundred to over 1,000 mg of electrolytes per hour, depending on sweat rate, heat, acclimatization, and individual physiology.

Drinking pure water can dilute electrolytes further, weakening electrical signals. Fewer muscle fibers activate and it takes longer for them to reset between contractions. Movements become slower, shakier, and less precise, and you risk slipping into junk volume where reps feel harder but fail to stimulate progress.

During exercise, thirst isn’t a reliable signal that it’s time to drink. The sensation often lags behind your actual needs, especially when you’re going hard. Many folks don’t feel dehydrated until beads of sweat are rolling.

A better signal: your phone’s timer. Plan out when to drink, and how much, and stick to that schedule, even if you don’t feel thirsty.

Share

Join the Baddest MF in the Gym Newsletter

Be the first to know about new collections and exclusive offers.